Distinguishing malignant cells in a single-cell project can be a very time-consuming task. Particularly, malignant cells are heterogeneous and often display misleading expression signatures, which can be further obscure by tumor microenvironment or treatment features. In addition, some malignant cells are closely related to their normal counterparts (e.g., lymphoma).

How can we define malignant then? For this purpose, researchers have leveraged copy number variation (CNV) analysis, i.e., considering that only malignant cells should display these somatic events. A fair assumption.

Nowadays, many software statistically infers CNV load using single-cell transcriptomics data, such as InferCNV or CopyKAT. However, while these methods are useful, we can point out a few bottlenecks in their assumptions. Essentially, these methods assume that gene expression changes can be indicative of underlying CNVs. Further, InferCNV relies heavily on the accurate identification of reference (normal) cells. If the reference cells are not correctly annotated, this can lead to incorrect CNV inferences. CopyKAT detection is limited to CNV events based on changes in read depth across the genome. Finally, both methods are not suitable for analyzing rare subclone structures, i.e., they expected expanded subclones that share similar genotypes.

Fortunately, new methods can leverage supplementary data or distinct statistical assumptions. On this note, we would like to introduce, Numbat. Numbat can be used to:

- Detect allele-specific copy number variations from scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics;

- Differentiate tumor versus normal cells in the tumor microenvironment;

- Infer the clonal architecture and evolutionary history of profiled tumors.

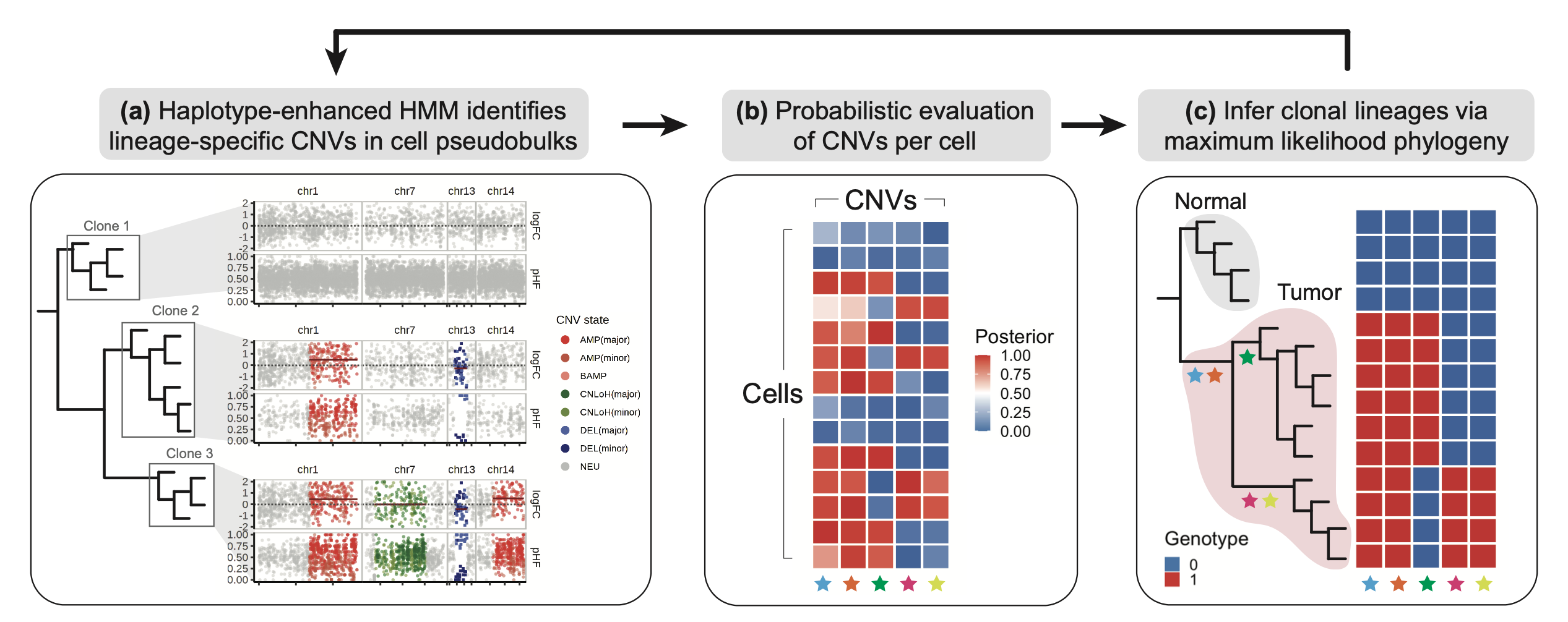

Numbat integrates haplotype information obtained from population-based phasing with allele and expression signals to enhance the detection of copy number variations from scRNA-seq. Cool, but what that means?!

In short, Numbat capitalizes on the allele imbalance approach to determine expected deviations caused by CNV events, i.e., an allele that deviates from normal proportion (1:1 ratio of paternal and maternal copies). This is done by phasing the single-cell reads using reference panels, such as 1000G and TOPMed. We could think about it as a “fine-mapping” step that shows single-nucleotide polymorphisms proportion across the single-cell reads. Therefore, alleles displaying imbalance proportions should be derived from CNV events. Did you gotcha it?

Now you have the principle, we can think this model is expanded into the haplotype level (multiple SNPs inherited together), and it incorporates expression changes related to genes across distinct cell populations. The distinct cell populations are essentially pseudobulk matrices- the authors mentioned that it was a way to overcome sparse coverage in scRNA-seq data. To note, it is a fairly common strategy for enhanced signal detection in single-cell studies.

Thus, Numbat’s model can jointly understand changes in the expression level considering how likely these changes are associated with CNV-related events. It is not only about expression fold-change deviations across probabilistic states but also about whether these deviations are supported by phased data on the pseudobulk level. What does that bring to the table?

The authors provide a few examples and validations displaying the value of their model (Teng Gao et al. 2022). But, for me, it considerably decreases subjectivity in selecting malignant cells (or even subclone structures) in my data. For instance, we are not using a reference based on annotated cells, which are very prone to human error, but a population-wise reference. Also, it potentially elucidates rare subclone structures by incorporating a maximum-likelihood step to capture evolutionary relationships between single cells.

But, what do you think bioinformaticians? Read the paper and, please feel free to reach out!